Few directors have enjoyed as successful a run as John Carpenter did from the late 70s to the late 80s. The writer-director-composer cranked out nine notable theatrical flicks from 78 to 88, and while not many of them were theatrical hits, they’re all now considered classics, either of the bona fide or cult variety. The 90s, however, were not so kind to the man. Starting with the ill-fated Memoirs of an Invisible Man, which was a difficult production and, ultimately, a box office bomb, Carpenter struggled to mirror the success he’d enjoyed in the 80s. There’s no doubt that some of the titles have their supporters: In the Mouth of Madness is a genuinely entertaining nightmare of a movie, and his Showtime anthology Body Bags is enjoyable, if fairly forgettable – save for Carpenter’s extremely amusing performance as our undead host. And while yours truly is not a fan, you can’t deny Escape from L.A. can be considered a guilty pleasure… depending on the sequence, anyway. Lost in the shuffle is Carpenter’s remake of Village of the Damned, the 1960 chiller that was an adaptation of John Wyndham’s novel The Midwich Cuckoos. If there’s one movie in Carpenter’s filmography that hasn’t built up a following of any significance, it’s this one, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth another look – especially for those of us who’ve really only seen it the one time. And on that note, how and why did this remake go awry? Hide the children – especially the white-haired ones – because we’re going to find out just WTF Happened to John Carpenter’s Village of the Damned.

Village of the Damned had been pegged for the remake treatment long before Carpenter got involved. In fact, it was the success of Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers in 1978 that convinced the rights holder, Lawrence Bachmann, that the time was right to remake the film. Bachmann lamented he wasn’t allowed to properly adapt John Wyndham’s novel in the 60s thanks to heavy censorship; in those days you couldn’t even mention impregnation, let alone abortion. Obviously, the remake did not get off the ground at that time, and it would take another decade before it gained some momentum.

The project eventually wound up at Universal Pictures, and found a champion in the executive vice president of the studio, Tom Pollock. In a Variety article from April 1990, it was announced Tom Holland, coming off Child’s Play, was in talks to direct the film. Alas, Holland never stepped behind the camera for it. Another notable name in the genre came in to take the reins: Wes Craven, who’d made several movies with the studio, including Shocker and The People Under the Stairs. While it’s unknown how far advanced the talks were between Craven and Universal, evidently the negotiations fell apart and the director walked away from this particular village.

Around that time, John Carpenter was trying to get his remake of The Creature from the Black Lagoon out of the swamp and into the production at Universal. While there was a script and even creature designs from the legendary Rick Baker, the project stalled at one point and never regained steam. As Carpenter had a deal with Universal, he was still under contract to direct a picture for them. Tom Pollack approached Carpenter with Village of the Damned seeing a natural fit between the creepy material and the filmmaker. Carpenter saw the project in very simple terms, later admitting in an interview that the movie was quote “an obvious choice,” and “a pretty easy movie to make.”

The script given Carpenter was written by David Himmelstein; it was the screenplay Wes Craven was working on before departing. According to Carpenter, the script had deviated greatly from the central ideas in Wyndham’s book and the subsequent 1960 movie. Carpenter found that the screenplay had even gotten rid of the idea that the phenomenon befalling the small town was the result of an alien invasion. In addition, the children were telekinetic in addition to being telepathic, something Carpenter apparently didn’t care for. Carpenter reasoned that there was no need to stray from the source material, and took to re-writing the screenplay himself to bring it closer to its roots.

Ultimately, Carpenter’s movie would end up being an incredibly faithful update of the original – with an interesting twist: Carpenter found that the original film mainly took place from the point-of-view of the male characters, and he thought the new one – understandably – should focus more on the women who suddenly find themselves pregnant and then giving birth to eerie alien children.

Carpenter immediately figured out the perfect location for production: in and around Point Reyes, California, about 50 miles north from San Francisco. Carpenter knew the area well: he had a house there, which he purchased not long after shooting a bulk of The Fog in the town. As the director put it in an interview, “you can stand anywhere, put the camera down and shoot, and you’ve got it.” A few scenes from The Fog and Village of the Damned were even shot on the same block.

Unfortunately, some of the locals didn’t appreciate their private paradise being disturbed by the likes of a Hollywood production. Supposedly, some folks were doing their best to sabotage the filming process, using methods such as firing up lawnmowers or chainsaws nearby while the crew was trying to record sound. Allegedly there were even some break-ins to the equipment trucks. While production continued in the neighborhood until the picture was wrapped, it was a somewhat sour experience for Carpenter, who considered the place his second home.

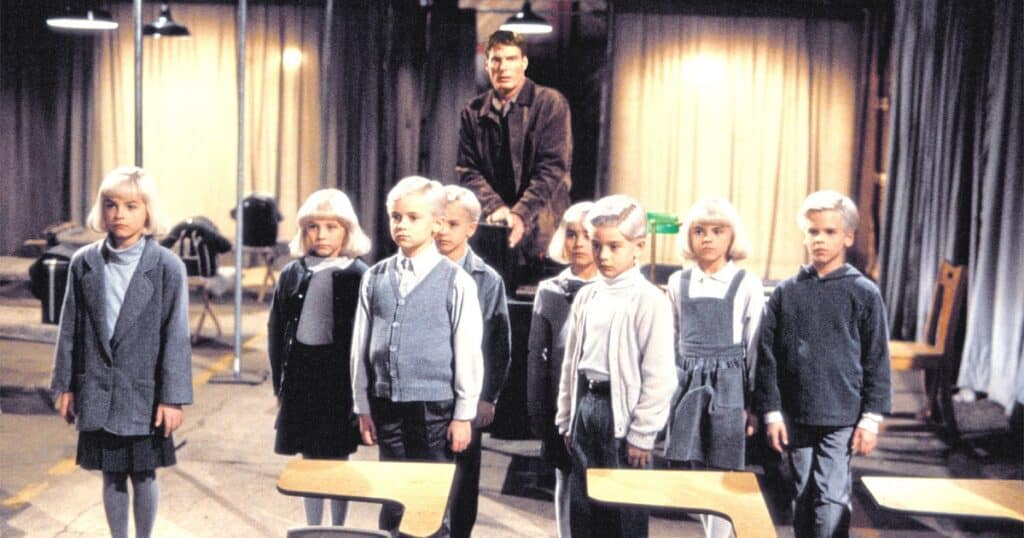

Cast in the film were Christopher Reeve, having put the Superman cape aside many years earlier; Cheers star Kirsty Alley, more known for her comedic chops at the time than her dramatic ones; Crocodile Dundee’s main squeeze Linda Kozlowski; and Luke Skywalker himself Mark Hamill, making this his second collaboration with Carpenter after appearing in Body Bags.

Obviously the ensemble of children playing the “damned” alien tykes would be crucial to the success of the movie. One young actor who climbed aboard was Thomas Dekker – who would later go on to play John Connor in the Sarah Connor Chronicles and appear in the Nightmare on Elm Street remake. Dekker later recalled that during auditions for the part, the other children would go out to play while he would stay behind and attempt to learn his lines. Since his character in the film is something of an outcast thanks to his humanity, Dekker staying away from the other children endeared him to the producers and got him the role.

Playing the main antagonist would be Lindsay Haun, then nine years old. Lindsay recollects auditioning many times for the part, which had its challenges in terms of the language the character speaks. The villainous child has the intellect of a genius, so Lindsay had to grapple with the complicated dialogue which was filled with words and concepts she didn’t understand. Haun would also fondly remember working with Christopher Reeve, who she said treated her like she was a professional on his level, something she always appreciated.

Understandably, aside from having chemistry with each other on the screen, one of the main requirements for the young actors was being able to nail the critical death-stare the children break out whenever they’re ready to inflict some damage. All of the kids auditioned had to give their best death-stare into the camera, and if they were able to properly intimidate, they had a leg up in nabbing the role.

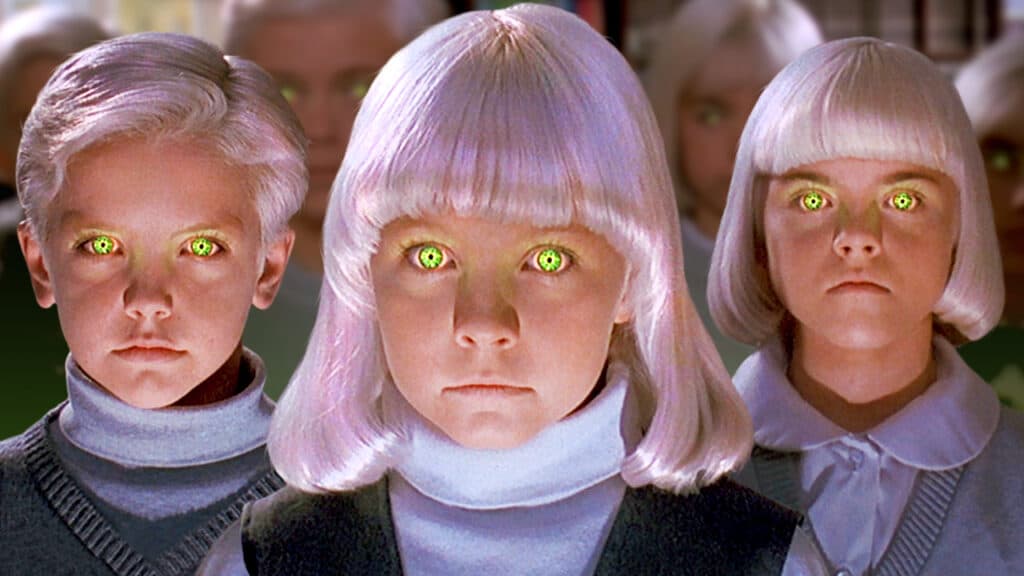

In order to achieve the signature white hair the alien kids rock, all of the children had their hair dyed blonde, then spray-painted white. While several critics would mock what they thought were bad wigs on the young actors, those bleach-blonde locks are the real thing. The kids would even travel around in a group sometimes, freaking out the locals.

To get the children to be in lockstep with each other, as the aliens basically all share the same brain, Carpenter relied on his longtime friend Peter Jason, who’s appeared in They Live and Prince of Darkness for the director. In addition to playing a role in Village of the Damned, it was up to Jason to get his young co-stars on the same wavelength, so that they’d move and react in the exact same way. Jason marched the kids around singing a military-style song, acting as a pseudo-drill instructor for the young cadets until they were one little unit.

Another signature of the alien children is when their eyes glow right before they do something destructive. Initially, Carpenter wanted all of the children to wear black contact lenses, which would then light up via CGI whenever the kids were up to no good. However, it quickly became clear that the contacts were going to be severely uncomfortable for the kids, so the idea was scrapped. Eventually, the eyeball effect was done digitally by Industrial Light and Magic.

Doing practical effects on the film were KNB, the busiest effects house in Hollywood. While creating corpses and gory wounds was nothing special for them, one challenge did present itself for an ambitious yet ill-fated sequence. Soon after the alien babies are born, there was to be a scene where all of the infants stood up by themselves and looked in the same direction, which would certainly be an alarming sight for any parent or nurse. KNB created three animatronic babies for the sight gag and shot them standing up and turning their heads three separate times, as it would all be put together in post-production. But for reasons unknown, the sequence was never completed and left on the cutting room floor. It’s possible Carpenter simply didn’t dig how those fake babies looked.

It would turn out that more scenes were to be trimmed or outright dropped from the film by Universal; one scene involved Thomas Dekker’s empathetic character learning how to play piano, while another saw the alien children lay waste to a group of teenage bullies. The studio apparently meddled with the film in post-production to the extent that Carpenter’s buddy Peter Jason didn’t consider it Carpenter’s film anymore; other actors similarly felt as though large chunks of the movie had gone missing, causing continuity and character problems. While Carpenter remained magnanimous regarding his collaboration with the studio, it would appear as though Village of the Damned‘s issues might be blamed more on Universal than Carpenter.

The studio gave the film an April 28, 1995 release date; considering it had wrapped in November of ’94, there was not a ton of time for post-production work. While the film most likely had plenty of things going against it, no one could have foreseen the tragedy that was about to rock the entire nation: on April 19th, a domestic terrorist’s bomb destroyed a federal building in Oklahoma City. The Village of the Damned crew were actually in New York City doing press for the film when the Oklahoma City bombing happened. Suddenly everyone’s minds were focused on that terrible event, not so much anything at the box office, let alone a movie like Village of the Damned which was grim and violent – not to mention the fact it ends with a barnful of small children exploding.

Village of the Damned opened in fifth place its first weekend and quickly petered out at $9 million domestic, not even coming close to its reported $22 million budget. In an interview many years later, Carpenter admitted he was not passionate about the film and that it was a contractual assignment that he had to do, though he was proud of the performance Christopher Reeve gave in it.

Thankfully for the iconic director, he has a host of better films to his name – everyone is allowed a clunker or two, after all, and when you have a filmography like Carpenter does, a film like Village of the Damned is as rare as having a telepathic alien baby.

A couple of the previous episodes of WTF Happened to This Horror Movie? can be seen below. To see more, head over to our JoBlo Horror Originals YouTube channel – and subscribe while you’re there!

The post Village of the Damned (1995) – WTF Happened to This Horror Movie? appeared first on JoBlo.

Leave a Reply