INTRO: What is the first movie that comes to mind when you hear the name Elisabeth Shue? Do you think of her as the Karate Kid’s love interest? The babysitter who went on an adventure through downtown Chicago? The Oscar-nominated prostitute from Leaving Las Vegas? Chances are, the movie that comes to mind is not Link. A horror movie where Shue shares the screen with a homicidal orangutan that’s passed off as being a chimp. Link isn’t very well known, but it should be. If you haven’t seen it, it’s the Best Horror Movie You Never Saw.

CREATORS / CAST: Link (watch it HERE) was directed by Alfred Hitchcock devotee Richard Franklin, an Australian filmmaker who, for a while, looked like he could be one of the best sources for new Hitchcockian thrillers once the Master of Suspense had passed away. Franklin had even been friends with Hitchcock, having met him while attending film school in California. He got his directing career started in the ‘70s, making the Western sex comedy The True Story of Eskimo Nell and the softcore sex study Fantasm. Not to be confused with the Don Coscarelli horror classic Phantasm. Then he shifted gears and started following in the footsteps of his hero. He teamed with screenwriter Everett De Roche to make the 1978 sci-fi horror cult classic Patrick. The following year, he optioned a short outline, presumably written by Tom Ackermann and future MacGyver creator Lee David Zlotoff, for a horror film that would have been like Jaws, but with chimps. The story wasn’t entirely there, though. So Franklin set it aside and focused on making the 1981 thriller Roadgames, starring Stacy Keach and Jamie Lee Curtis. A project that came about when De Roche suggested making a version of Hitchcock’s Rear Window that would take place in a moving vehicle.

It was De Roche who cracked the story for Link. Not surprising, since he already had killer animal movie experience, having written the 1978 nature run amok film Long Weekend. He read a National Geographic article by chimp expert Jane Goodall that shook up everything people had believed about chimps. As Franklin explained to Fangoria magazine, Goodall saw “the cannibalizing of young chimpanzees by one particular mad female chimp. She observed actual inter-tribal warfare between two groups of chimps. The whole ’60s idea of man being the only animal to make war against its own kind was suddenly thrown out the window. That, to me, was a really interesting idea for a good thriller.”

The script De Roche wrote follows American zoology student Jane Chase, who attends the London College of Sciences. She gets a job working as assistant to anthropology professor Doctor Steven Phillip – not at the college, but at his isolated home on the English coast. A house that sits on the edge of a cliff, in farmland that’s patrolled by dangerous wild dogs. Phillip has to do his work at home because the university won’t let two of his three chimps anywhere near the campus. Six-year-old Imp is okay. He seems to be gentle and harmless, despite his habit of killing birds and cats. But the mature female Voodoo is wild, and 45-year-old Link, who likes to wear clothes and smoke cigars because he used to be called the “Master of Fire” in a circus… well, there just seems to be something off about Link.

Things fall apart soon after Jane arrives at Phillip’s house. The doctor makes a call about selling Voodoo because she can’t breed anymore and having Link put down because the old boy is getting increasingly strange. Link doesn’t care about Voodoo, but he murders Phillip to protect himself. He dumps the body in the well and pushes the doctor’s car over the cliff. It takes a while for Jane to realize the doctor is dead, but it doesn’t take long for her to realize that Link is weird. He even likes to creep on her when she’s trying to take a bath. And soon enough, she finds out he’s dangerous. A killer. She needs to find a way out of this situation, which is complicated, since Link has destroyed the phones and vehicles, and she can’t walk to town because of the wild dogs roaming the countryside.

Franklin was going to start filming Link in Australia in 1981. The funding was in place. But then, a major distraction: he was offered the chance to direct the sequel to the Hitchcock masterpiece Psycho. It was an opportunity he couldn’t turn down. Psycho II turned out to be a better movie than anybody expected it to be. It was so well received, it led to Franklin and writer Tom Holland re-teaming on the spy adventure Cloak and Dagger. That one wasn’t a box office success, so Franklin circled back to Link, which he hoped people wouldn’t compare to The Birds, so it wouldn’t look like he was just copying Hitchcock with every movie he made. He wanted his killer animal movie to be more rooted in reality than the fantasy of The Birds. But the two films do share a crew member: Ray Berwick, who trained the birds for Hitchcock’s movie, also trained the apes for Link.

The film was set up at Thorn EMI Screen Entertainment, which was, during that period, headed by Verity Lambert, known for being the founding producer of the Doctor Who series. Production took place in Scotland, although the story is set in England and that setting was very important to Franklin. He said that, “in mood, tone and look, it resembles Psycho II, crossed with the English setting of Jane Eyre. … The English setting to me was essential. I wanted to contrast the primitivism of jungle animals with Old World values, high culture, and civilization.”

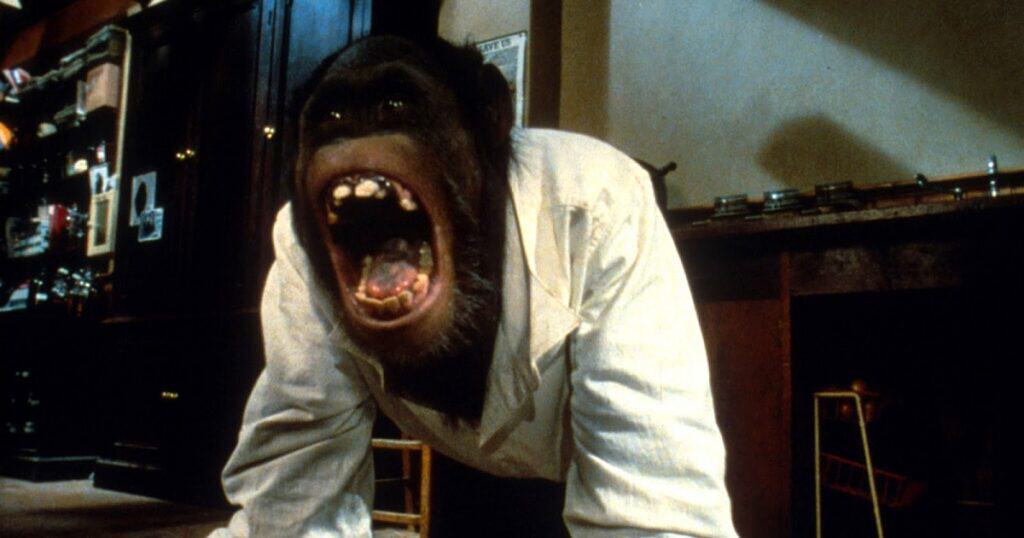

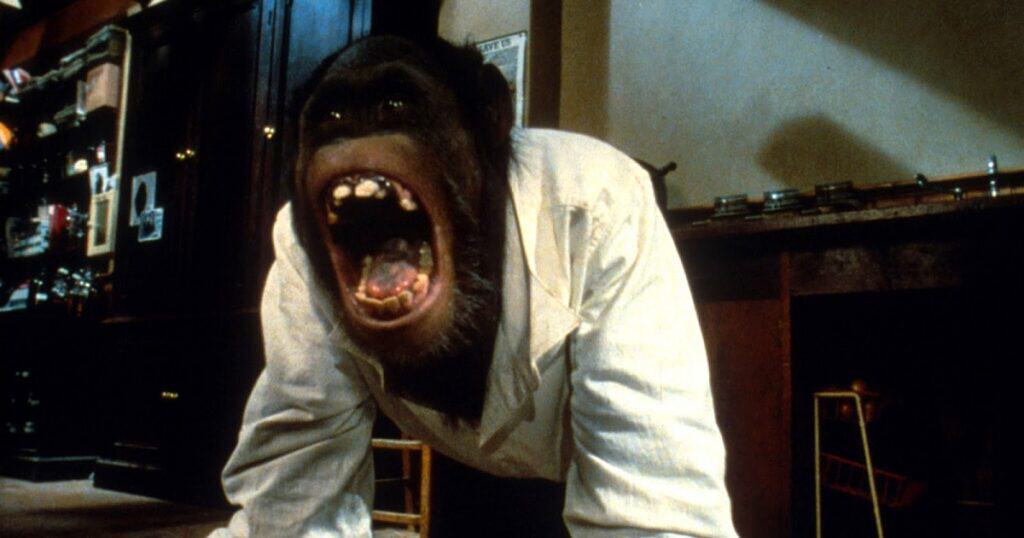

Elisabeth Shue, fresh off The Karate Kid and the short-lived TV show Call to Glory, was cast as Jane Chase, her first lead role in a feature film. Terence Stamp plays the ill-fated Doctor Phillip. Kevin Lloyd shows up as chimp dealer Bailey. With Steven Finch, credited as Steven Pinner, playing Jane’s boyfriend David. And Richard Garnett and David O’Hara as his friends Tom and Dennis, who are just there to boost the body count. But aside from Shue and Stamp, most of the human actors have very brief roles in the film, and there’s still an hour left in the running time when Stamp makes his exit. So the majority of the film is carried by Shue and some apes. Imp is played by Jed, with Carrie as Voodoo. Then there’s Link, who is referred to as a chimp, even though he’s clearly an orangutan. This ape actor was named Locke. His fur was dyed a darker color and he was given prosthetic ears so he would look more like a chimp. It didn’t do any good, but it was better than the alternative. Throughout pre-production, Franklin was pressured to have the chimps played by people in costumes and makeup. He refused because he wasn’t making a fantasy film. This was meant to be rooted in the reality of what chimps are capable of. So he got to make the movie with actual apes.

Shue would go on to earn an Academy Award nomination for Leaving Las Vegas, but watching this movie will make you think the Oscars should have a category for Best Ape Acting. Locke turned in an incredible performance as Link. Of course, this is mainly the work of Franklin and his editors. Locke didn’t know what kind of story his trainer had him acting out, but he was able to give the filmmakers the movements and expressions that they built his screen performance out of. And when the camera cuts to Link, you can see the wheels spinning in his mind. He’s plotting. Scheming. Or perving, in the case of the bathroom scene.

BACKGROUND: There’s an old saying that you shouldn’t work with animals, but Franklin didn’t have much trouble working with the apes on Link. Production even went more smoothly than he was anticipating. The real problems didn’t arise until post-production. That’s when Franklin was informed that Cannon Films, the U.S. distributor, would be cutting eight minutes out of the film. It got worse when Thorn EMI Screen Entertainment went up for sale… and was purchased by Cannon. Now that they owned Link, they decided to cut out five more minutes. The film was now thirteen minutes shorter than the director intended it to be. Which may not have been the worst thing. Even at the final running time of one hundred and three minutes, Link feels slightly longer than necessary. Cannon really could have gotten a bit more out of it. But, as far as Franklin was concerned, his film had been compromised.

Before the Halloween 1986 release, Franklin was considering making another ape thriller about an anthropologist getting caught in the middle of war between chimpanzee tribes in Africa. But it wasn’t to be. Link was not as well-received by critics as Roadgames, Psycho II, and Cloak and Dagger were. And the box office numbers weren’t great, either. Made on a budget of six million dollars, Link earned less than two million in U.S. ticket sales. It made the video and cable rounds and got a bit of a cult following. In 2021, an extended cut that boosted the running time to one hundred and twenty-five minutes was released in France. But Link has never become as popular as it deserved to be. Even those who were involved with it wrote it off. Franklin dismissed it as an unsatisfying experience on almost every level. In a 2021 interview, Shue said her career wasn’t going well when she did “a not-great horror movie called Link.” But we have to disagree with her. Link is a great horror movie.

WHAT MAKES IT GREAT: The set-up is perfectly simple. A young woman trapped in an isolated house with a dangerous ape. Dialogue in the early scenes lets us know how much trouble she could be in, as we hear that chimps are eight times stronger than humans and are told a story about a man being torn to pieces by a chimp who was just happy to see him.

Franklin does a great job of building the suspense as Jane gradually figures out what’s going on. And Shue did a great job of carrying the film for the long stretch where she’s alone with the apes. She was only twenty-one years old during production, just starting out in her career, and she proved she was capable of being a strong lead. Hopefully she’s proud of her work on the movie, even if she’s not a fan of it.

There are plenty of other killer primate movies out there, and this ranks up there as one of the best, along with the 1932 Murders in the Rue Morgue and George A. Romero’s Monkey Shines. It’s unique in its approach to the concept, as it builds up Link in the same way it might if the character were human. He’s lurking around, a silent creeper. We know it’s only a matter of time before something terrible happens. We’re waiting for the moment when he’s going to fully snap. And once Jane comes to understand what Link is capable of, it kicks off a sequence that’s around thirty minutes of almost non-stop action and thrills.

BEST SCENE(S): That is, of course, the most entertaining section of the film. And judging by the way it was shot, it feels like Franklin was having a lot of fun bringing it to the screen. When Jane attempts to shoot Link through a door, there’s a cool shot of her through the hole left in the door. There’s a cave in the cellar that leads down to the sea, and when Jane and Imp make it down to the water, you might think they have just escaped from Link. But Franklin lets us know the action is far from over by cutting to a helicopter shot, the song “Apeman” by The Kinks kicking in on the soundtrack as we fly over to the road that leads to the house to see that Jane’s boyfriend and a couple friends are about to arrive and meet Link for themselves.

Then we get to watch the body count increase as Link deals with the new arrivals. And Franklin was particularly pleased with a moment where he had Link pull someone through the mail slot in the front door.

Jane’s boyfriend David is injured by Link. She has to help him by putting a makeshift splint on his leg, adding a humorous element to the final chase sequence as we watch this injured guy with a leg splint try to escape from Link, getting tossed all over the place and probably injuring himself some more. The only questionable shot in here comes when Link chases Jane and David upstairs and they try to hide in Phillip’s lab, which has a metal door. To follow Jane and David into the lab, Franklin has the camera going over the top of the wall, breaking the reality and revealing this is just a set. This is something that’s done in movies all the time, but some may find it jarring.

PARTING SHOT: But a movie is doing pretty well when you’re only left questioning one shot and whether or not a couple extra minutes could have been taken out. Overall, Link is an intriguing, well-crafted thriller with good human and primate performances and a score by Jerry Goldsmith that is occasionally reminiscent of the work he did on Gremlins. This film proves once again that Richard Franklin was indeed a Master of Suspense. Unfortunately, it was the last movie he made in the ‘80s. And in the ‘90s, he decided to change directions. Rather than continue making genre movies, he moved on to the arthouse. He would eventually re-team with Everett De Roche on the 2003 horror film Visitors, his last film before he passed away in 2007. But that run he had from Patrick through Link really makes us wish we had a lot more Franklin thrillers to watch.

So if you haven’t met Link yet, head out to that isolated home on the English coast and spend some time with him. He’ll do some tricks for you: smoking cigars, setting fires, murdering people. He puts on a great show, and it’s definitely worth checking out.

A couple previous episodes of the Best Horror Movie You Never Saw series can be seen below. To see more, and to check out some of our other shows, head over to the JoBlo Horror Originals YouTube channel – and subscribe while you’re there!

The post Link (1986) Revisited – Horror Movie Review appeared first on JoBlo.

Leave a Reply